Housing is the Key

“Housing is the key to reducing intergenerational poverty and increasing economic mobility. Research shows that increasing access to affordable housing is the most cost-effective strategy for reducing childhood poverty and increasing economic mobility in the United States. While many developers have coined the term “affordable”, most low and very low-income residents cannot afford what has been deemed as affordable housing. Instead of qualifying for the newly developed affordable units, residents are being pushed further into poverty, and worse, homelessness. We need to create housing that will be made affordable to San Bernardino’s most low-income populations.”

– National Low Income Housing Coalition

In San Bernardino, one of the long-existing problems has been access to affordable housing

In San Bernardino, community members experience a vast difference in quality of life, which is heavily determined by local costs of housing. Due to our current economic climate, home ownership has become increasingly difficult. For some in San Bernardino, securing housing is an impossibility while others are forced to make severe sacrifices over periods of 5-10 years while saving for a down payment on a home. As a result of rising costs of living and stagnant wages, any potential mortgage savings are at risk when a medical emergency, accident, death, job loss or a combination of the above. In any of these cases the possibility of home ownership becomes majorly set back unless residents have access to some type of capital such as years’ worth of savings, a vehicle they can sell, or the like. In some cases, personal emergencies even mean the loss of current housing, in which case future home ownership is lost as an option altogether.

The struggle for a stable home

This state of vulnerability to housing insecurity over a single emergency expense illustrates the concept of ‘housing poverty.’ Housing poverty refers to the situation of having a place to live or rent, but having the costs for that housing amount to more than 30% of an individual’s or family’s total income. In most cases, the rest of the income is further split between basic human living needs such that further cutting expenses to meet continually rising housing costs creates even more risk. Further highlighted by Tables 2-6, costs of living, including housing costs, rise faster than local wages. On top of this, families are forced to compete with incoming residents who are able to take advantage of lower local housing costs than more affluent neighborhoods. This in turn adds to the rising number of homeless residents in the community.

For residents in San Bernardino, the average or market rate for a 2 bedroom, 1 bath apartment in the city is $1390. This means that someone would have to take home $4700/month in order to be beyond the housing poverty threshold. According to the 2020 census, the median household income in San Bernardino is $45,834/annually. The reason for the 30% distinction in the housing poverty threshold is that costs of living outside of housing which include the basic human necessities such as food, clothing, water, and transportation are just as subject to the changes affected by inflation and its relation to wages. For Homeowners, the median listing price for a house in San Bernardino is currently $449,000. And, in order to qualify for a mortgage loan on a house purchase one must have saved 3.5% ($15,715) – 20% ($80,000) of the purchase price for the downpayment.

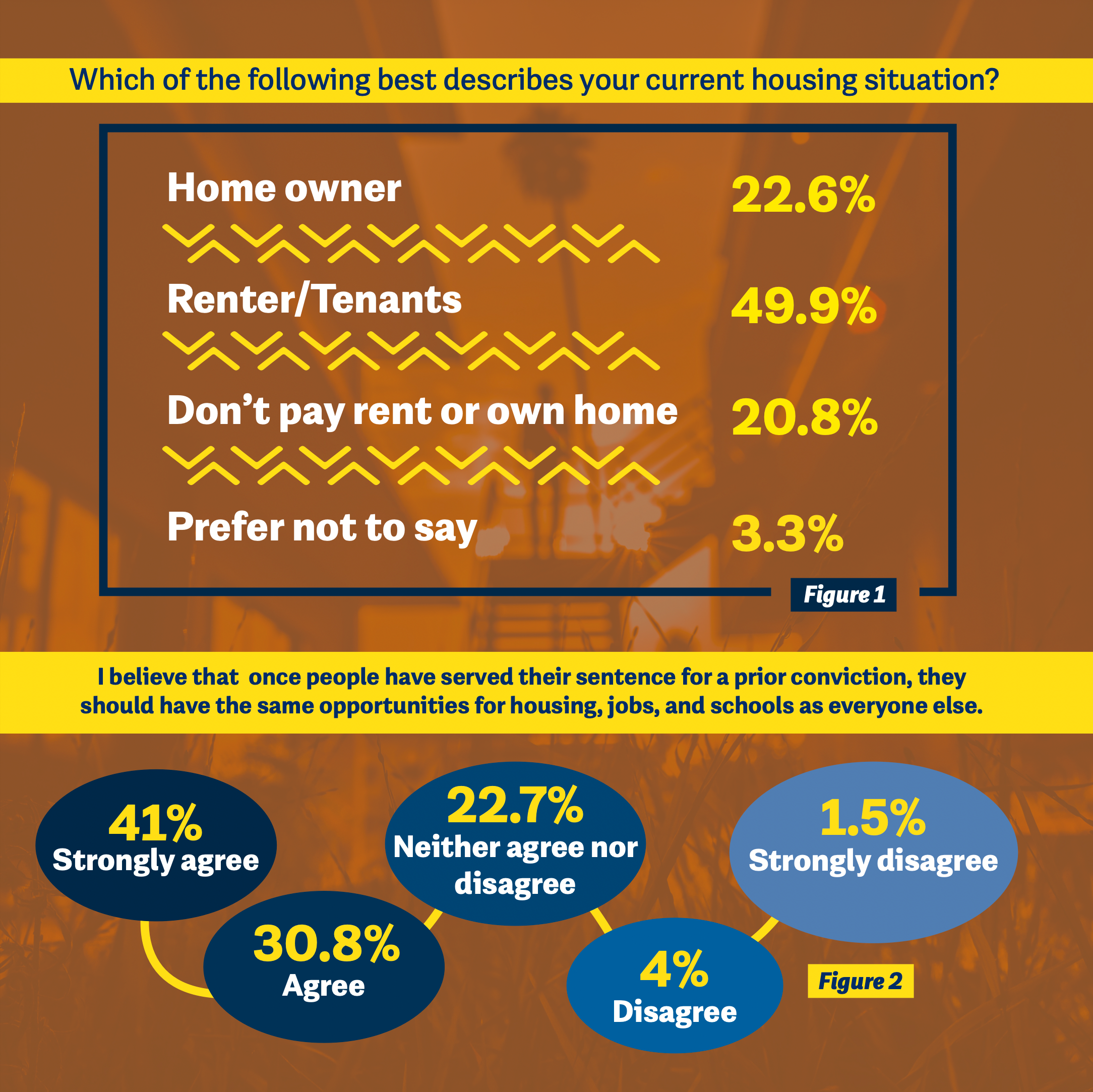

As shown by our findings in figure 1, owning a house is not affordable for individuals living below the average income in San Bernardino. Mobile Home Residents similarly require a down payment or lease for a home where the tenant also pays rent for the lot in addition to their mortgage. This results in housing costs similar to that of a traditional rental, but with added complicated restrictions. For example, Mobile Home Leasing Offices in San Bernardino manage their own financing companies which specifically target immigrant families to lock them into 30 year mortgages at predatory rates of 14% or higher. However, these leasing offices also hold them to strict regulations creating the opportunity to evict the families, before or after they finish paying for the home, so that they may repossess the unit and sell to a new buyer. Thus, a looping economic engine is created for the company owners at the cost of families’ livelihoods. As figure 1 from our survey data shows, 20.8% of people in San Bernardino do not rent or own a home, compared to the 22.6% that enjoy home ownership. Further research and analysis is needed to understand how much of the 20.8% are youth, or unhoused community members, or both.

Click to zoom

According to the 2020 SB County Homeless Point In Time Count Report, we have 1056 people who are homeless and living in the streets of the city . This constitutes over 1/3rd of the county’s total documented unhoused population, a number that has steadily increased due to 30 years of political obstacles. Historically, elected officials have opposed the development and approval of affordable housing strategies in San Bernardino because of the false narrative that Affordable Housing will attract poverty and more homelessness. As a result of this, they have discouraged unhoused people from moving to the city, as well as the development of strategies that might help alleviate and solve the problems. Additionally, elected officials have refused to apply for federal funding grants specifically designed for homeless support services and shelter creation in the city. They not only deny their own communities of funding sources created specifically for their situations, but in turn criminalize homelessness by displacing them and taking away any resources they do have when occupying public spaces. This plays a larger role in the poverty cycle created by politicians, property owners, and corporate entities that take active part in property speculation.

While this highlights the need for an affordable component to housing, our community members face a myriad of barriers to even qualify to rent and access the inadequate amount of housing that does exist in the region. This housing scarcity creates competition between all community members, which then raises rental prices and housing costs beyond the fair market rate. This in turn can lead someone into homelessness, which, because of criminalization, may result in community members falling into the prison industrial complex, or being deported.

Formerly incarcerated individuals (FII) are returning home to San Bernardino County with little to no housing available. Since February 2020, the jail population has decreased by 30%, a result of Prop 47 and the Covid-19 pandemic.7 The need for affordable housing, especially among the formerly incarcerated population, is steadily increasing, yet availability is decreasing. Lack of affordable housing in San Bernardino is one of the contributing factors to recidivism. Additionally, formerly incarcerated individuals continue to face post-incarceration discrimination which further prevents them from obtaining stable housing, and potentially throws them back into the cycle of poverty.

While many FII are encouraged to be honest about their criminal histories, honesty often continues the cycles of homelessness and hopelessness that they experience. One resident explained, “As a former parolee, I just feel that they tell you before you get out to be honest when it comes down to any job applications or any type of paperwork because it can come back on you. At the same time when you are honest you don’t want someone to turn that honesty against you when you need a house to stay in, and you need somewhere to lay your head you know, so you don’t want that to backfire on you. And being a parolee, people are going to judge, you can’t stop them from judging, it’s me, I have to take that step to prove them wrong.”

Another community member noted the importance of having access to affordable housing as a mother post-incarceration. They explained:

“Affordable housing means everything to me, especially coming from incarceration for over 10 years, so it’s like the job outlook for me is not very broad and is very slim. I can’t be picky, because I got to accept anything that is offered to me at this time you know, so if I have to worry about how much rent is that’s just more stress on me. So I would say that it [affordable housing] means a lot because then that’s one thing, one stressor, I don’t have to worry about. I can focus on getting my sobriety right, getting myself back to where I need to be, where I can take care of myself and my daughter who is 17.”

Among the different challenges to finding affordable housing, some FII participants highlighted the mental and physical tolls of not having housing. Many experience feelings of stress, being forced to live in insecure places and having to take anything available even if it is not a safe place. For example, one resident explained:

“I think affordable housing could help adults in so many ways develop mentally and emotionally and become stable. I think it’s very important because it takes off a lot of stress from an individual. As a mother to have a stable environment to work every day and build that confidence you have that stability for your babies so that way we as parents can be good role models and feel stable. We can focus on how to bring our kids up and focus on our children’s education. If we’re stressed and stuff sometimes it can be hard to even focus on those important things for children.”

Looking at figure 2, these numbers reveal the majority of our community members believe that once people have served their sentence for a prior conviction, they should have the same opportunities for housing, jobs, and schools as everyone else.

If we are going to see a community that prioritizes equal housing opportunities for all community members we must start with making more housing affordable and available to formerly incarcerated individuals. Individuals returning home from incarceration are parents, primary caregivers, children, and are looking to take care of their families. Families need access to housing that is affordable and does not disqualify them due to their past. Specifically, we need to set-aside funding that prioritizes FII and is based on their income.

Some of the fights and wins we have taken on in terms of statewide policy initiatives include San Bernardino passing one of the state’s first COVID Eviction and Displacement moratoriums to provide the basic protection from eviction for families who contracted COVID-19, and fell behind on rent as a result. We then followed up with legislative pushes that resulted in the creation of an Emergency Rental Assistance Program which allocated funding to further support those families who had to deal with other costs after such an illness, or the loss of income providers in their households. However, the reality is that this isn’t enough. These are protections and services that should have existed long before the pandemic and the loss of life. COVID proved to us that the difference between being homeless or not could be less than the two weeks off from work needed to fight the COVID virus.

Recently, a 44 Acre downtown redevelopment project was announced in San Bernardino in the midst of COVID. This announcement has resulted in a drastic upward shift in property values and created a perfect storm for property speculation in the area. This has further exposed the flaws of our housing market and the poverty cycle that holds many of our community members hostage.

The Road to a Home

It will take a long time to get the economic capital needed to truly address this issue in a way that prioritizes our community individuals, their health, and their wellbeing. This holds true for our local economies, as funding invested in affordable housing pays off tenfold by leveraging public and private resources to generate income, including resident earnings and additional local tax revenue, which in turn supports job creation and retention. The solutions for these issues begin with the creation of powerfully organized constituencies and political champions and their ability to make changes in policy, and financial decisions where our community members’ voices are echoed and valued over economic profits for the already wealthy.

We propose a multi-pronged housing strategy to address the housing crisis and the way it affects different people at different income levels.

This includes funding for homeless shelters, transitional housing, support services, affordable housing development, policies that allow for the creation of alternative housing models, supporting more types of housing cooperatives, Community Land Trusts, accessible home buyer education, stricter taxes on vacant lot speculation owners, and policies that enable formerly incarcerated individuals to have access to affordable housing.

We support the expansion of affordable housing in major developments such as the Carousel Mall redevelopment in downtown San Bernardino, a site that could be transformative to the city and its housing development.

We are opposed to criminalizing homelessness, including use of policing to harass people and evict residents from their homes.

The city has opportunities to build and expand affordable housing but has not taken full advantage. The city must prioritize accessing state level funding that exists to build housing and support the houseless.